From the President: My Rural Roots

en espagñol

en espagñol

January is a time for beginnings, a time to pause and remember what first called us to this work. As I enter 2026 as President of WONCA, I find myself reflecting on my own beginnings in family medicine, and how firmly they are rooted in rural communities.

My family medicine roots are rural.

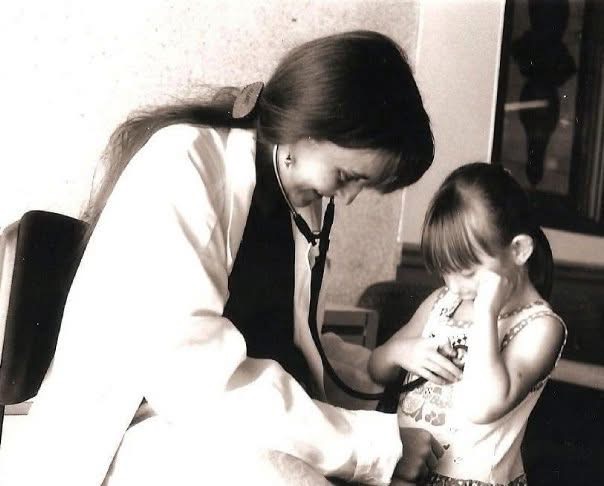

As a trainee at the University of Iowa Family Medicine Residency Program, from which I graduated in 1996, I cared for patients in Lone Tree, Iowa- a small town of about 1,300 people- where medicine was never just about diagnoses or prescriptions. It was about relationships, trust, and continuity. In rural practice, I learned quickly that when you care for one person, you often care for an entire family, and sometimes for generations.

I also learned that this continuity did not rest on the physician alone. The front desk staff and nurses knew patients as neighbors, coworkers, cousins, parents, and grandparents. They knew who had lost a spouse, whose child was struggling, who needed an extra word of reassurance, and even who might be dealing with the consequences of a “rough” time at the only bar in town the night before. They knew who needed help navigating life beyond the exam room, and who carried the weight of thousands of acres of land to care for. They were -and are- essential members of the care team, holding deep knowledge of the community and helping weave healthcare into the fabric of daily life.

Photo credit: Barbara A. Caldwell, EdD,1997

After residency, I practiced in Muscatine, Iowa- a community of 20,000 people shaped by agriculture, industry, the Mississippi River, and extraordinary resilience. There, I learned what strength looks like in rural life.

I cared for farmers who needed things “fixed now,” because harvest does not wait. I met people who milked cows in twenty-degrees-below-zero, long before dawn, and still showed up for care when something was wrong.

When a tornado hit town, the community came together to rebuild the homes destroyed by the winds. When my car slid into a ditch under two feet of snow, it was a patient who pulled me out with his tractor.

I cared for factory workers who repeated the same movements minute after minute for ten-hour shifts, often injured by that repetition, and for women who picked meat from bones at the packing plant, their hands shaped by years of constant pulling.

I cared for truck drivers who crossed the country to pick up harvests or goods from local industry and then carried them back to Western states, days away. Muscatine was the one place they knew they would stop long enough to see a doctor while their trucks were being loaded.

I also cared for migrant farmworkers who crisscrossed the United States following agricultural seasons—from Oregon to Florida—and who were in Muscatine County for the timing of different harvests. They helped bring food to tables across the country, harvesting melons, vegetables, corn, and soybeans, and working in dairy, poultry, and hog operations—often doing work that cannot be mechanized. Their lives were marked by mobility, hard labor, low pay, and uncertainty, yet they showed the same resilience and dignity I saw throughout the rural community. Caring for them required flexibility, cultural humility, and advocacy, and reinforced for me that rural family medicine must meet people where they are.

In Muscatine, family medicine mattered in a very real way. When resources were limited and distances were long, the family doctor—working alongside nurses, staff, and emergency teams—often became the bridge between everyday life and lifesaving care.

The work demanded presence, breadth, and constant readiness, along with quiet prayers that a helicopter could land on the helipad during a blizzard to take a patient whose needs exceeded what our small hospital could provide.

I scrubbed into the operating room to first assist the only surgeon in town whenever one of my patients needed emergency surgery. I delivered babies, many of them, and cared for those same families across generations, including their great-grandparents. I supported patients and families at the end of life, often in moments of profound intimacy and trust.

One morning, I delivered a baby and immediately afterward cared for his grandmother, who went into severe respiratory distress while still in the delivery room.

I covered the emergency room, caring for whatever came through the doors, knowing that in a rural community the family doctor must be prepared for everything and for everyone.

Two years after leaving Iowa, I received a phone call from the granddaughter of one of my patients, the 89-year-old matriarch of a large farming family.

I knew her well. I had cared for her for years. I had walked her through the decision to undergo an aortic valve replacement because, as she told me, she “still had farming bookkeeping and cooking to do in support of her five farming sons.” I had delivered several of her grandchildren, bought their produce at the farmers’ market, and once diagnosed one of her sons with an acute myocardial infarction after years of ignored anginal symptoms, sending him urgently to the Cath lab.

“Grandma Josie has been very ill,” her granddaughter said. “She wants you to tell her if it is okay to let go and stop fighting. She wouldn’t rest until she heard your voice. She wanted you to know she tried hard to stay longer.”

They placed the phone next to her. “The whole family is here,” her granddaughter added. “We were just missing you.”

I spoke softly, holding back my own tears, imagining the large family gathered around her bed. Holding presence. Holding love. “It is okay, Mama Josie,” I said. “Everyone is going to miss you, but everyone is going to be okay. You taught them strength. It is ok to go.”

I could hear her breathing slow, soften, and then stop.

Moments like this reaffirm what rural family doctors around the world understand. Our role is not only to provide care, but to be present, prepared, and knowledgeable, and to earn trust when it matters most.

Rural family medicine reveals the full scope of our discipline. It spans birth and death, prevention and crisis, continuity and coordination. It often means managing chronic illness and responding to emergencies at the same time. It requires working closely with others, making careful decisions, and taking responsibility for patients and for communities. This is comprehensive, person- and community-centered care at its core.

Those early years shaped my professional identity and values. They taught me humility, the importance of staying current and learning continuously, and the power of deep listening. They also opened my eyes to the inequities rural communities face, inequities that persist across countries, cultures, and health systems.

Today, as President of WONCA, I meet family doctors from rural and remote communities in every region of the world. Whether they practice in small towns, islands, mountainous regions, or other underserved settings, their stories feel familiar. They speak of dedication in the face of scarcity, of problem-solving rooted in place, and of deep commitment to the communities they serve. Migration within countries and across borders touches all of these settings, reminding us that mobility and vulnerability are shared global realities.

An estimated 3.4 billion people live in rural areas of the world. Rural family medicine is therefore not peripheral to our discipline. It is foundational. It reflects continuity, coordination, and compassion in action, and it reminds us why primary care matters. Strong health systems are built from the ground up, with family medicine at their core, everywhere, not only in urban areas.

As we begin this new year, I warmly invite colleagues from around the world to come together in community, reflection, and shared purpose. WONCA Rural 2026 will be a unique opportunity to celebrate rural family medicine and general practice, learn from one another, and strengthen our global movement. I encourage you to join us and learn more at ruralwonca2026.com

My family medicine doctor journey began in rural Iowa, but its lessons continue to guide my leadership today.

With gratitude and solidarity,

With gratitude and solidarity,

Viviana Martínez-Bianchi, MD, FAAFP

President, World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA)