In my View: Prof Val Wass

Photo: Val Wass chairs a workshop

Photo: Val Wass chairs a workshop

Our meetings at World Health Assembly (WHA) with the medical students’ association (IFMSA) and with the Youth Hub and the Young Leaders Network reinforces to us the need for good undergraduate medical training, to encourage more people into our profession. There are a range of obstacles, right across the globe, to achieving the numbers of trained family doctors needed to achieve Universal Health Coverage. The earlier medical students are exposed to community based primary care, the more likely they are to choose family medicine as a career. So, this month, I have asked Professor Val Wass, globally renowned medical educator, Chair of the WONCA Working Party on Education, and also WONCA Member At Large and Honorary Treasurer, to give her views on how the education of medical students needs to adapt to the changing health environment.

Donald Li, WONCA President

Transforming education to develop health systems in an interdependent world1: the role of WONCA.

WONCA World Family Doctor Day 2019 “caring for you for the whole of your life” reminded the world of the importance of Family Doctors. As highlighted in the WONCA Seoul 2018 declaration

2, they “must be trained to give comprehensive care across the lifecycle (from cradle to grave) in a person-centred way.” Holistic, compassionate generalist care lies at the heart of all we do.

The Seoul declaration states that family doctors can (and must) address “the emerging needs of ageing populations and the increase of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) at the Primary Health Care (PHC) level”

2. Strengthening PHC and achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) remains at the core of our strategy. The Seoul statement urges countries “to invest in training skilled Family Doctors through the development of academic capacity starting at the medical school level.”

2 In my view these two statements are intrinsically linked. Yet, globally, medical education has failed to recognise this.

1 We can now collaborate across the WONCA networks to reform undergraduate and postgraduate education and tackle the changing needs of population health. Without this, UHC will, I believe, be unachievable.

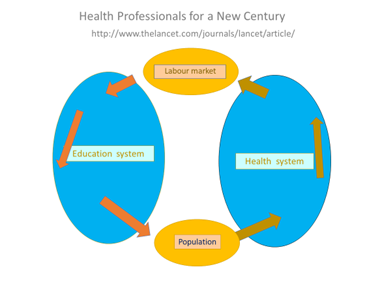

The Lancet report on Health Professionals for a New Century states categorically that “20th century educational strategies are unfit to tackle 21st century challenges.”

1 The authors argue that changing population health drives a need for a different labour market; a workforce able to care in the community in a generalist way, that is,. more Primary Care. What medical education has failed to do is counterbalance this with the radical change in curricula to produce this workforce

1. (Figure 1 at right)

As long as medical education is based in hospitals, taught in the silos of specialisation and fails to foster the holistic generalist values of PHC, we will continue to produce a secondary-care oriented workforce. The ongoing shortage of Family Medicine doctors will not improve. I believe the secondary-care-dominant model, as perpetuated worldwide, is harmful. Medical education globally must adapt to health care delivery needs in the local context.

But we, as doctors, too must change. We need to address our own professional boundaries

3, embrace societal needs and anticipate the roles of future doctors alongside other health care workers. This requires new professional values centred on social accountability, opening the borders between science and the humanities, addressing human rights, equity and justice, and supporting students to learn PHC skills, e.g. undifferentiated diagnosis, handling risk, uncertainty. As educators we have a crucial teaching role, yet this is not embedded in hospital dominated medical schools.

Unless we change our approach and raise our status within the medical school hierarchy, the world will continue to face an imbalanced workforce. In England, challenged by a shortage of General Practitioners, a report was commissioned on how to support careers for General Practice (GP) in medical schools. “By choice not by chance”

4 revealed multiple factors negatively influencing career choices in GP. An unexpected finding was that the low status of GP as a career starts even in primary school. Lack of exposure to PHC and GP role models in the context of learning, not understanding what a General Practitioner does, a strong undermining of family medicine as a career option within the hospital environment, and failure to promote the academic potential of GPs were among the factors mitigating against it. Quality exposure to exposure to PHC is positively transformational; a finding now well documented in the international literature.

As Nelson Mandela so wisely said: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” We have a great opportunity to positively act on the Seoul declaration. It both highlights the changing population needs and pleas for trained skilled family medicine doctors. This fits well into the Lancet report model (Figure1 above) of linking the two within our strategy and regional organisational structures. Now is the time to transform medical education.

References:

1: Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world.

Lancet. 2010

www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61854-5/fulltext

2: WONCA :

Seoul Declaration 2018

3: Wass V. Southgate L. Doctors without borders.

Acad Med. 2017; 92 (4): 441-443 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001618

4: Wass V, Petty-Saphon K, Gregory S. By Choice not by Chance 2016

www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/By%20choice%20-%20not%20by%20chance.pdf